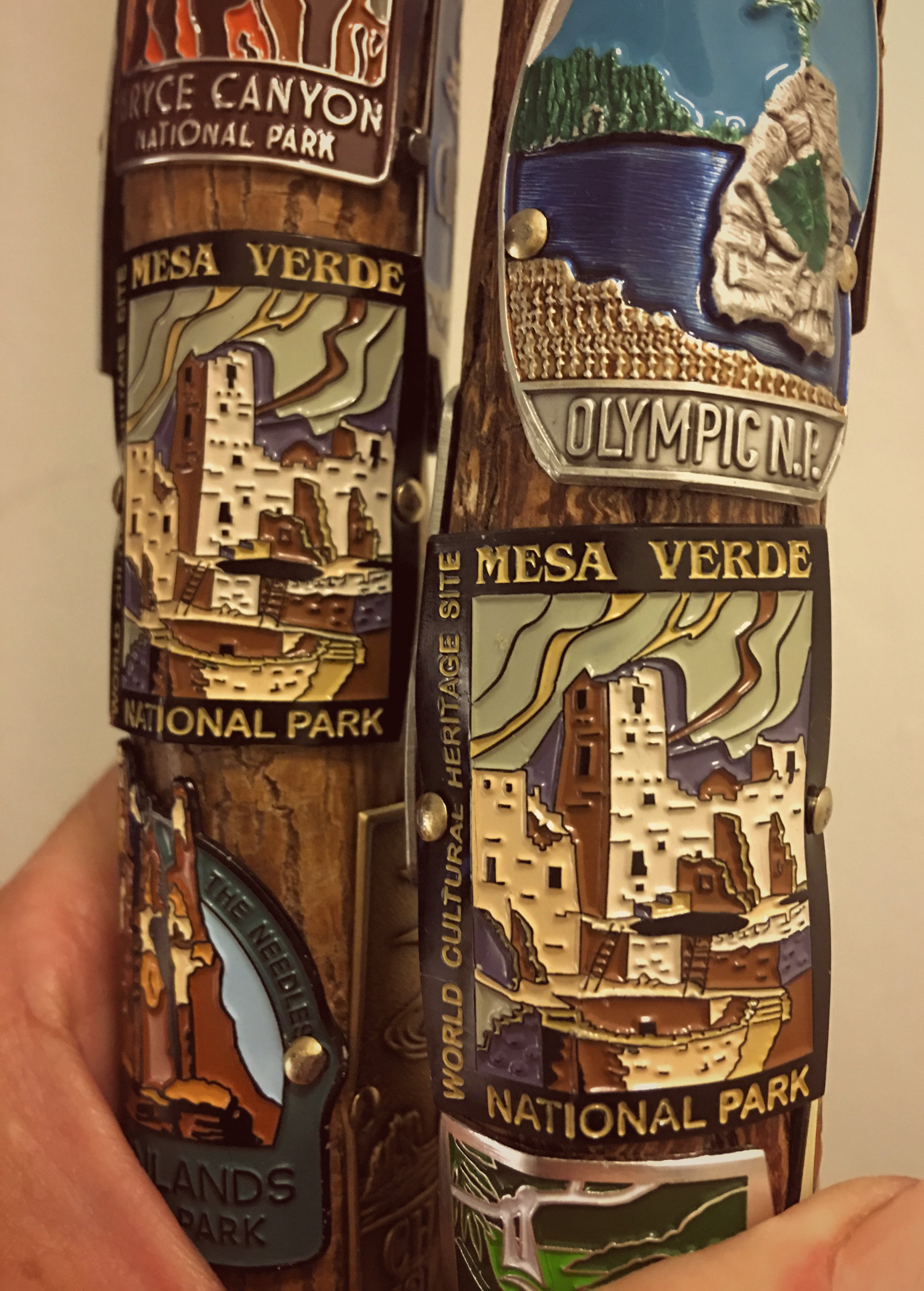

Mesa Verde National Park, Colorado, USA | Park 48/59

“The falling snowflakes sprinkling the piñons, gave it a special kind of solemnity. It was more like sculpture than anything else … preserved … like a fly in amber.”

Mesa Verde National Park: a Legacy of Stone and Spirit

Park Ranger David Nighteagle offers a song to his ancestors inside Cliff Palace.

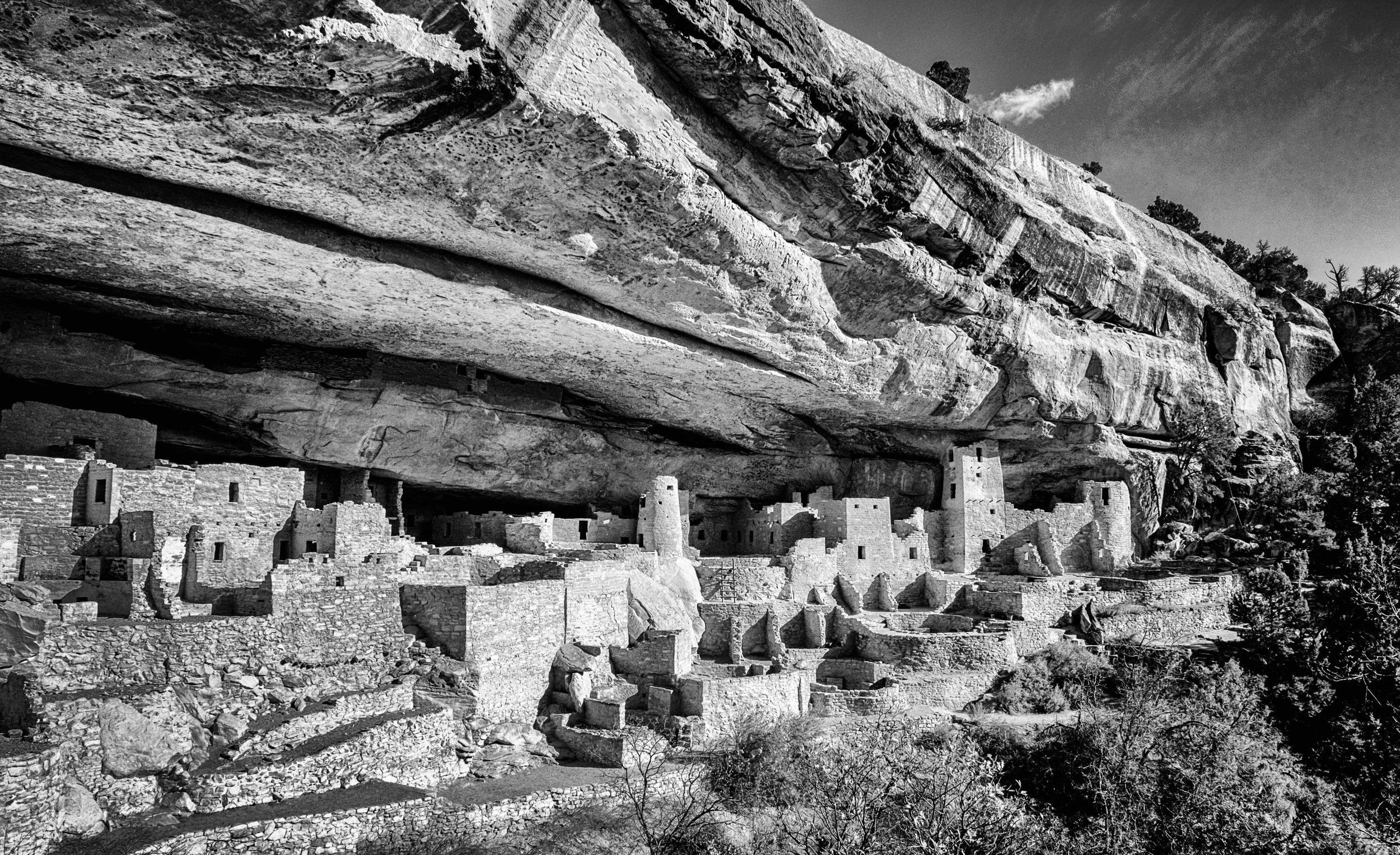

There are 59 national parks in the United States and Mesa Verde in southwest Colorado is the only one that was created to safeguard the history of a people and a cultural resource. When Teddy Roosevelt signed the bill into law establishing Mesa Verde as a national park in 1906, his remarks were clear: the park would ‘preserve the works of man.’ The works he was referring to were, most notably, ancient villages built upon sandstone ledges on steep cliffs perched 2,000 feet above the Montezuma Valley.

This park earned its name from the pinyon pine and juniper forests that blanket the ceiling and slopes of the Navajo Canyon.

Mesa Verde is Spanish for “green table”—named for the pinyon pine and juniper forests that blanket the ceiling of the Navajo Canyon—where nearly 5,000 archeological sites and 600 cliff dwellings built by the ancestral Puebloan people between 550-1300 A.D. remain today. The sophistication of the dwellings is notable as only sticks, stones, and bones were used to create all of the sites; the tools evolving over time to advance architectural methods of the day. Some of the sites are small, contained one-room units found atop the high surfaces of the canyon walls (the green table) and others are multi-story palaces (some with up to 200 rooms) found nestled in the steep rock faces somewhere between the mesa* and the canyon floor. The location of the dwellings were strategically chosen and served multi-functional purposes—positioned far enough from the flat-top above that they provided protection from invading groups, while enclosed enough that they maintained solar warmth and energy within the enclosures. To navigate between the mesa, the dwellings, and the canyon floors, the ancestral Puebloans would climb (they are arguably among the first free-climbers in North America) while also making use of hand-made ladders that allowed them to travel to and fro. The structures were also used for ceremonial purposes.

The end of an era…

For seven centuries, the ancestral Puebloans thrived until they abandoned their homes around 1300 A.D. Archeologists have multiple theories as to why they left the area, the most likely determination being that drought wiped out their crops while impending war with invaders subsequently drove them south to the area that now belongs to the state of New Mexico. Another contributing factor to their departure was possibly due to the fact that they over-hunted and overused natural resources in the area. Whatever the reasons for their complete departure, by 1300 the natives had moved on from their dwellings, never to return. After that, what was once a bustling community and home to tens of thousands of people fell to silence, where their homes remained undiscovered for nearly 600 years.

Rediscovery…

A period of rediscovery occurred in the late 1800s, with a most remarkable find occurring in 1888 by a couple of cowboys passing through the area. Under a winter snowfall, they saw remnants of another era frozen in time… they had stumbled upon Cliff Palace, the largest and most comprehensive dwelling found to date in Mesa Verde.

Exploring Cliff Palace on a private guided tour.

The first of European descent to climb into the dwellings was geologist Dr. John S. Newberry on the San Juan Exploring Expedition in 1858. The first to photograph the ruins was explorer and noted geological survey photographer, William Henry Jackson, who documented Mesa Verde in 1871 and later showed his findings in exhibitions, capturing the wonder of his east coast counterparts. By that time, protecting the area as a national park had already been suggested by the Denver Tribune Republican, who detailed in an 1886 editorial the fear that "vandals of modern civilization" would soon devastate the cultural digs if interference was not implemented. Then in 1888, (incidentally, the same year the National Geographic Society was founded) Richard Wetherill and his brother-in-law Charles Mason rediscovered Cliff Palace. Together, they descended a makeshift ladder into the 150-room settlement and carefully collected materials that they planned to sell to museums to make some extra money. After falling in love with the palace, they turned their focus to lobbying efforts for protection of the area as a national park. Their efforts were unsuccessful, but they were able to attract attention from others who valued their find and were of significant wealth and effect and as such had a greater ability to move the needle of the U.S. government. It would take many years of effort, and then one day, a very special leader (President Theodore Roosevelt) with a strong focus on conservation would elevate the protection at Mesa Verde. The result is that those sites remain unspoiled for all of us to go and see today—dwellings that are among the best preserved of their kind, continuously and impeccably cared for by archeologists, historians, geologists, anthropologists and National Park Service professionals ever since.

Through their collaborative research they are able to uncover secrets of a site enfolded by mystery—a quest to unearth secrets of successes established by ancient farmers, navigation methods used to traverse villages nestled on steep cliffs; better understand tribal relations in the area and geologic occurrences; and also processes used to architect entire villages without the use of number systems or a written language (as they none at the time.) These are all studies that continue to benefit all of our lives on Earth every day in some way.

To the common visitor, understanding comes though observance. Any one of us who ventures there can peer onto the memory of a once-bustling ancient civilization and imagine what candlelit glow once looked like while illuminating cliff-side villages towering on cliffs in this far-flung area of Colorado… the same way city lights illuminate modern cities today.

*According to NASA Earth Observatory, the Spanish given name mesa verde is not an accurate geologic reference. Per their website: Cuesta—not mesa—is the correct geological term for the dissected tableland found in the park, while mesas are flat-topped highlands with steep sides. Cuestas are flat highlands that have a gentle slope in at least one direction.

Spruce Tree House.

Exploring Today…

One of the coolest aspects of Mesa Verde is the sheer volume of cliff dwellings that are preserved inside of the park. There are also thousands of archeological sites on record, and there are certainly more that are yet to be found. For this reason, Mesa Verde is one of the most highly restricted parks in the entire system (walking off of established trails is entirely prohibited.) The beauty of such restriction is two-fold: 1.) you are blessed with the knowledge of impassioned rangers who seem to know everything about the past, present, and near-future of the park; and 2.) you know that this lone cultural resource is being fiercely protected—as we want all of the parks to be!

The archeological sites can be found on two mesas: Chapin and Wetherill Mesas, separated by the Navajo Canyon, where dwellings line the walls. Access to most of the best-known dwellings require that you take guide-led tours offered by the park service, where visitors enter the ruins by ascending and descending ladders and stone-made steps. Some of the most popular guided tours include the Balcony House, Long House, and of course, the Cliff Palace. To go to any of them you will want to get tickets at the Mesa Verde Visitor and Research Center in advance. The Spruce Tree and Step Houses can be explored freely. Other cool areas include the Far View Sites Complex where visitors can wander among archeological sites to survey well-preserved kivas and their inner workings, and catch a glimpse of one of our favorite finds, a petroglyph of a sun dial.

Some of the oldest archeological sites in the park exist at the Mesa Top Sites.

Petroglyph at Pipe Shrine House, Far View Sites Complex.

Quotable Images

Fact Box

52,074 acres | World Heritage Site | U.S. National Register of Historic Places Designation

The 26-foot Square Tower House at Cliff Palace.

Official name: Mesa Verde National Park

Date established: June 29, 1906

Location: Southwest Colorado, in the "Four Corners" area where Colorado, New Mexico, Arizona and Utah meet.

How the park got its name: "Mesa Verde" is Spanish for "green table" which refers to the green blanket of vegetation, pinyon, and juniper that lays across the top of the Navajo Canyon. The name was given by Spanish explorers.

Iconic site in the park: The best known cliff dwelling in the park is Cliff Palace, the largest of all of the dwellings and the crown jewel of the national park. The first stone was mortared in 1200 A.D. and over the course of 20 years the settlement would grow to include 150 rooms and 23 kivas that would house an estimated 100 people until the site was abandoned in 1300 A.D. Among the most celebrated structures in the palace is the 26-foot Square Tower House, the tallest internal structure found in any of the dwellings at Mesa Verde. The natural sandstone that the village was carved out of is believed to have once been painted in bright colors.

To explore Cliff Palace, head to the park Visitor and Research Center to reserve your spot before driving an hour down park road to the Cliff Palace Overlook where you will join a ranger-led tour on a one-hour journey.

Cliff Palace in 1891, photo by Gustaf Nordenskiöld.

Cliff Palace in 2016, photo by Jonathan Irish.

Accessible adventure: There are two different auto-tours in the park that follow wild roads along mesas on either side of the Navajo Canyon. The most popular of the two is the 6-mile route on Mesa Top Loop Road which offers stops at accessible sites throughout where you can join park-led tours and step onto overlooks that peer onto ancient villages of the ancestral Puebloan people (including the Sun Point Overlook from where you can see Cliff Palace in a distance.) The 12-mile Wetherill Mesa Road on the other side of the canyon is a wild ride, bringing visitors from Far View to many scenic views that overlook four states. Wetherill is open only from May through October; and vehicle size and weight restrictions are in effect on both park roads so check National Park Service access areas on the official website to get more info before heading out. Both roads have steep grades, sharp turns, and offer great opportunities to see wildlife. Approximately 40 cliff dwellings can be seen from national park roads and overlooks.

A mule deer peeks out of the brush on Mesa Top Loop Road.

Mesa Top Loop Road surrounded by beautiful brush in fall 2016.

Peering onto the Spruce Tree House from an overlook on Mesa Hill Top Road.

Descending the Mesa Top Loop Road at sunset wields stunning views.

Balcony House.

Big adventure: The ranger-led Balcony House tour brings visitors through a variety of strenuous sections—down a 32-foot ladder, through a 12-foot tunnel on hands-and-knees, and on a crawl up a 60-foot open rock scramble before exiting a 10-foot ladder climb. The tour is only one hour long but it is the most adventurous dwelling tour available and allows visitors to explore kivas and plazas in one of the best-preserved sites in the park while breaking a sweat at the same time.

Did you know...

President Roosevelt established Mesa Verde National Park in 1906, the first park of its kind established to protect cultural artifacts and to preserve native American Indian history in North America.

It is estimated that 30,000 people lived in the area before it was abandoned around 1300 A.D.

Mesa Verde has the largest collection of ancestral Puebloan artifacts ever found—there are more than 5,000 archaeological sites and over 600 cliff dwellings documented in the park.

Common sites in dwellings and in archeological sites include terraces, kivas, farming terraces, field houses, reservoirs, ditches, shrines, ceremonial features, and rock art. Kivas are keyhole-shaped rooms used for ritual purposes rather than for daily activity.

Kivas at the Far View Site Complex.

Kiva is Hopi for "room underneath,” adapted by anthropologists and archeologists to refer to ceremonial rooms. They are found throughout Mesa Verde. Kivas are well engineered with ventilation systems to bring fresh air into the structures where ceremonial fires once burned in the center—also in the center is a small hole, called a sipapu, which represents an opening to the otherworld. Some kivas have underground passageways leading to other areas in the settlements.

Hopi Indians in Arizona and New Mexico are descendants of the Mesa Verde Ancestral Pueblo peoples.

Ancestral Puebloan people were hunter/gatherers. They excelled at basket weaving, farming (primarily corn, beans, and squash); crafting pottery with clay derived from sandstone, and tool making. They were among the best stonemasons of all native tribes.

The average lifespan of the ancestral Puebloan people was 32-34 years, years cut short due to infant mortality rates (it is estimated that half of the children born in the civilization died in the first few years of their lives.)

Doorways in dwellings at the Far View Sites in Mesa Verde National Park.

What you might think are windows in the dwellings are sometimes actually doorways. The average height of women of that time was 4'8"; men 5'2"-5'5”.

From the National Park Service—In the spring of 2006, all Native American human remains and associated grave goods in the park’s collection which were excavated within park boundaries were reburied. The reburial ceremony was a result of 12 years of consultation with the park’s 24 associated tribes, and was performed by both park staff and the Hopi tribe. Due to the sensitive nature of the event, and out of respect for the tribes, the reburial was closed to the general public and took place in an undisclosed park location. The repatriation was done in accordance with the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) of 1990.

Matate, sort of an ancient mortar and pestle, was made of natural materials found in the area to grind corn into cornmeal for eating. Soft sandstone was commonly used—which would granulate and mix into foods wearing down the teeth of the ancestral Puebloans.

Sandstone is softer than the human fingernail.

Desert varnish (dark streaks on rock created by oxidization) as seen above a dwelling from a park road overlook.

A “stabe” crew is consistently working in the park to stabilize rocky areas that change with the effects of erosion and with geologic shifting.

There is more to this park than archeological sites and dwellings. Forested areas are made up of Utah juniper, pinyon pine, and scrub oak and provide a healthy habitat for a variety of wildlife species, including deer, elk, bobcat, mountain lion, skunk, and badger, to name a few; and the birdlife in Mesa Verde is teeming (more than 200 species have been documented in the park.)

The main water source wasn’t found in rivers, streams, or lakes, but from water seeping from rock.

One of the first champions of the park was Virginia McClurg—a prolific poet and lecturer who grew awareness to the artifacts and subsequently founded the Colorado Cliff Dwellings Association—an all-women collective.

National Park Service Rangers at Mesa Verde are some of the most impassioned and committed in the Park Service, opening up a world of wonder to every visitor who enters the dwellings.

Colorado is known for its high elevation. In Mesa Verde it ranges from 6,900 feet and 8,572 feet.

Wildflowers bloom in the springtime, a popular time in the park in terms of visitation for photographers.

Cross-country skiing along Cliff Palace Loop is popular during the winter.

Scenes from the film Baraka (one of our favorites!) were captured in Mesa Verde National Park.

The USS Mesa Verde was the first naval ship to be named after a national park.

The Morefield Campground provides the only camping facility in the national park, with 267 sites for tent and RV/trailer camping (with only 15 hookups; open from May to October.)

Bring sturdy shoes and binoculars with you—so you can find your footing and catch great views of dwellings from canyon overlooks.

Looking for a 3-day itinerary in Mesa Verde? Colorado Tourism has one laid out and ready for short-term visitors intent on seeing the park in an efficient way.

Mesa Verde was named UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1978.

The park welcomes about half a million visitors a year.

A raven flies overhead at Cliff Palace, said to be a good omen to natives in the area.

The Chapin Mesa Archeological Museum teaches visitors about the ancient Native American culture through exhibits, lectures, and extensive artifact displays.

While this park is open year round, scientific research and stabilization efforts are common during low season. It is always a good idea to check park alerts before visiting so that you can get the most bang for your buck.

Don’t forget to download your park visitor guide before visiting Mesa Verde!

Can’t make it to Mesa Verde? Check out the webcam and go there right now!